Elizabeth Brumbaugh, Harker’s director of Learning, Innovation and Design, was selected last week to join the Google for Education+AI Fellowship.

LID

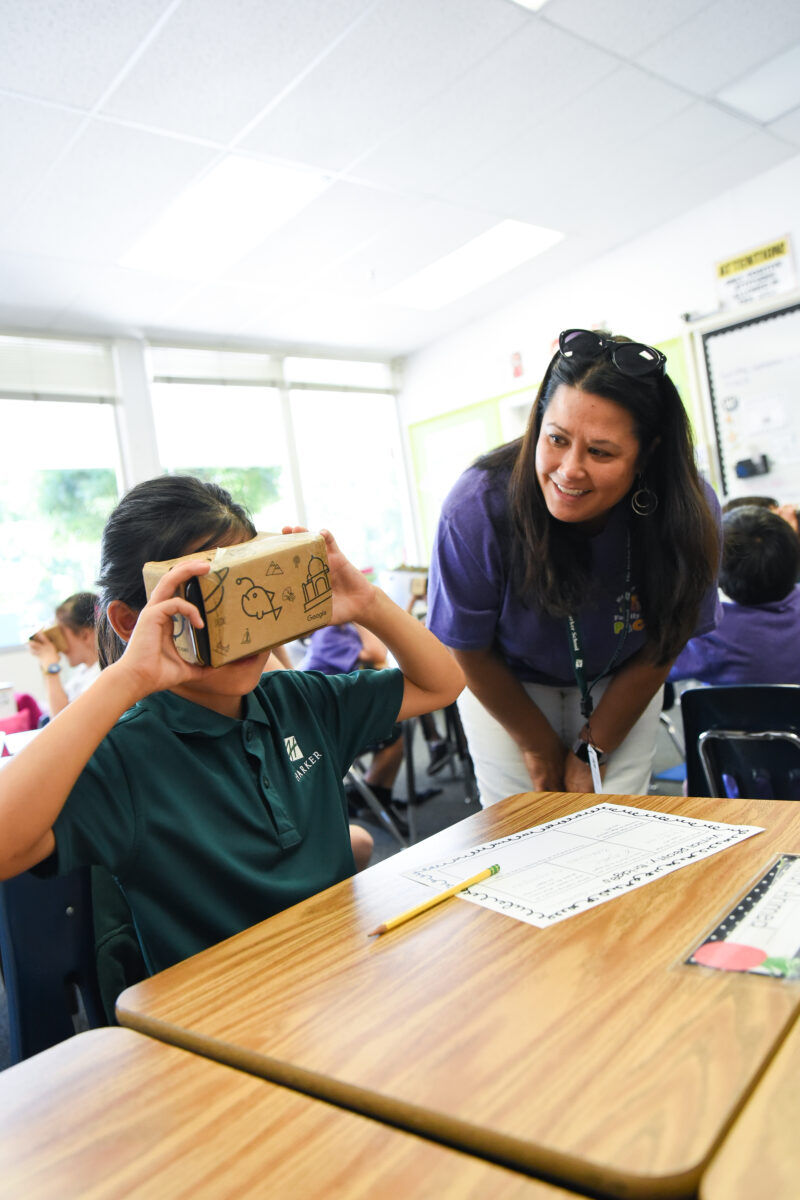

More Than Tech: LID helps teachers transform classrooms

Harker’s learning, innovation and design (LID) department has for years been a key driver of much of the technology and methods that have made the school’s classroom experience continually exceptional.