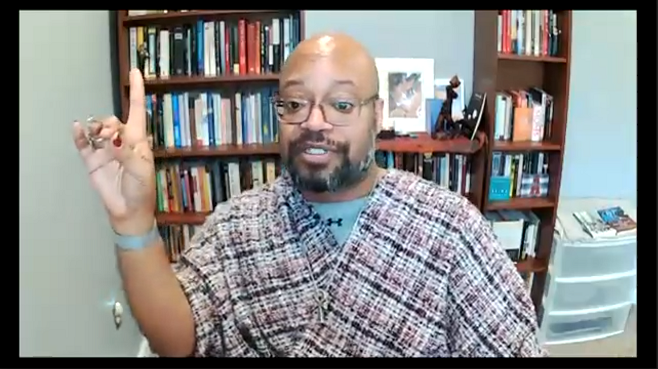

Last week, a special middle school assembly featured author and historian Jan Batiste Adkins, who shared the history of African Americans in the Bay Area and Santa Clara County area.

DEI

East Palo Alto Councilmember Antonio López speaks at MS assembly

The middle school marked the start of National Hispanic Heritage Month by inviting East Palo Alto City Councilmember Antonio López to speak at a special morning assembly.

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Harker: What it Means, Where it’s Headed

Student speaks at event for UN’s Commission on the Status of Women

Last week, junior Aneesha Asthana was on a panel of speakers as part of a parallel event to the United Nations’ 66th Commission on the Status of Women (CSW).

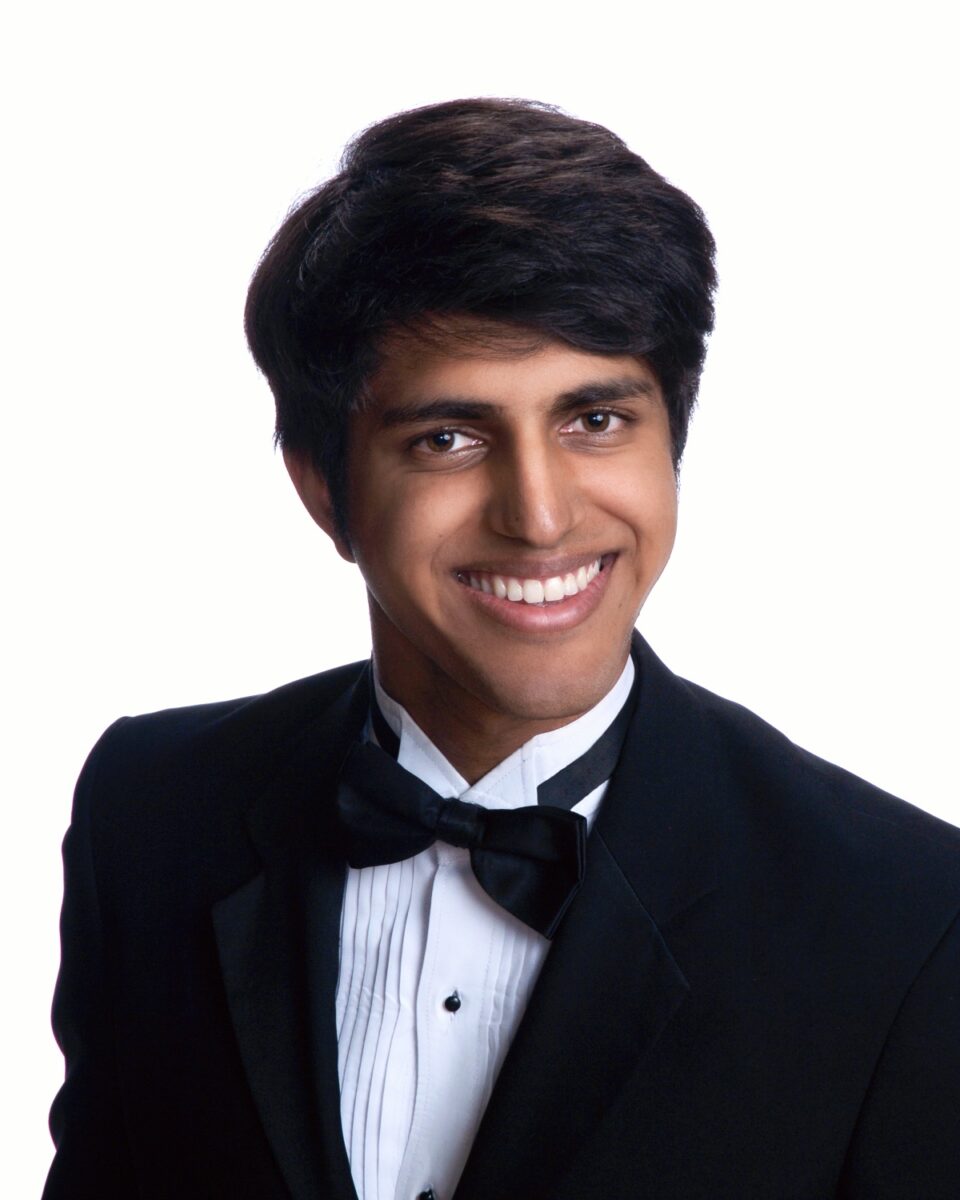

Bajaj ’20 co-authors two pieces published in medical journals

Two manuscripts co-authored by Simar Bajaj ‘20 were published in medical journals “Nature Medicine” and “The Lancet.”

Land acknowledgments extend to lower and middle school campuses

On Oct. 15, lower and middle school students viewed special presentations about the importance of acknowledging Indigenous land and the history of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, the direct ancestors of the Thámien Ohlone-speaking people, the original stewards of the land on which Harker’s campuses now rest.

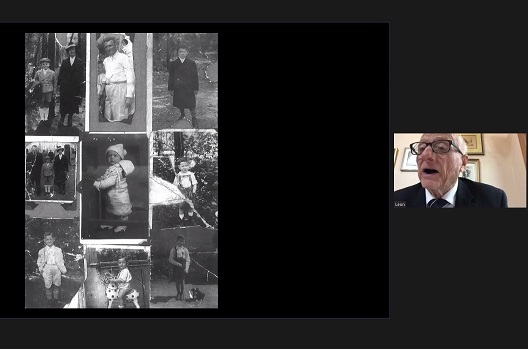

Holocaust survivor shares incredible story

Last week, the Student Diversity Coalition and the Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center hosted a special appearance by Leon, a Holocaust survivor who related his incredible story to the Harker community.

Muwekma Ohlone Tribe representatives visit for land acknowledgment unveiling

On Sunday, representatives from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe visited the upper school campus for the unveiling of the land acknowledgment monument that recognizes the land Harker’s campuses rests on as the ancestral land of Thámien Ohlone-speaking people.

Bay Area students, teachers attend Student Diversity Leadership Gathering

Tiffany Liou ’08 speaks on violence against Asian Americans

Tiffany Liou ‘08, now a reporter with the ABC-affiliated WFAA in Dallas, posted a video in which she speaks about the yearlong wave of violence against Asian-Americans.