This article appeared in the spring 2015 Harker Quarterly.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the inaugural issue of the journalism program’s magazine Wingspan in January 2015. Wingspan will publish four times a year, with in-depth news, features and design done by students. Harker Quarterly is proud to reprint this article on the Silicon Valley gender gap, which further explores the topic of women in technology (see also the winter 2014 HQ, page 6, “Inspiring Girls Who Code”).

by Kacey Fang, grade 12 and Elisabeth Siegel, grade 11

Photos and original layout by Shay Lari-Hosain, grade 11

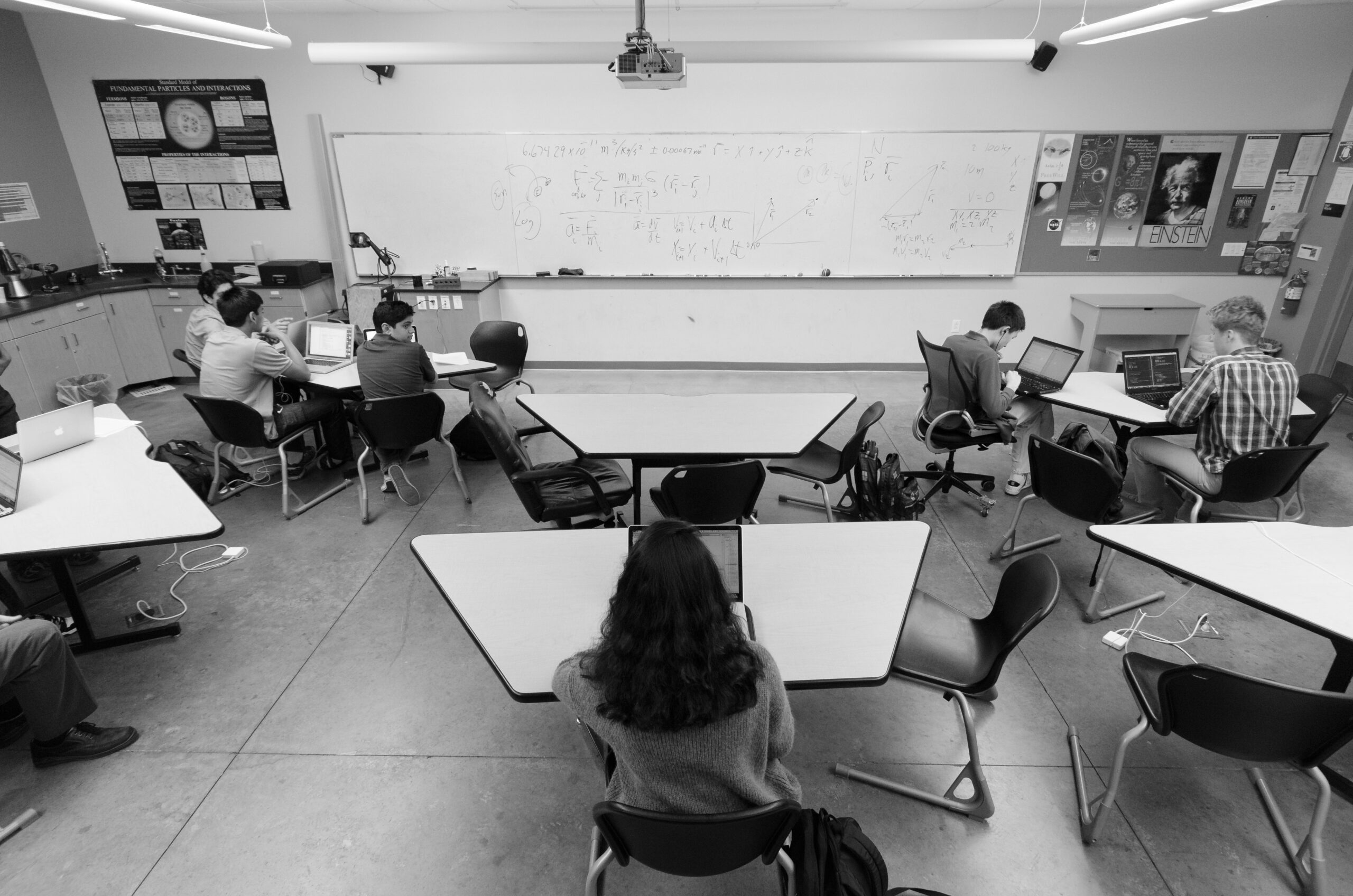

She sits down in the last open seat of the Neural Networks computer science class in Nichols Hall – middle table, last row. The two tables adjacent her and the three in front each have two to three of her male classmates clustered around them, immersed in code. The male teacher walks around, answering occasional questions.

These 11 boys had been junior Anika Mohindra’s companions in the advanced topics course she took in the first semester of her junior year. A post-AP class, Neural Networks introduces students to artificial neural network technology and its applications.

“I remember when I walked in on the first day, I thought, ‘Oh, I’m the only girl in this class,’ and that made me a little nervous,” Mohindra said. “I know gender disparity is a problem, so letting it affect me makes me feel a little deficient.”

Computer science (CS) department chair Dr. Eric Nelson taught the class the last time it was offered six years ago. With two degrees in physics, he has previously worked in corporate research environments and at astronomical observatories. He said that the students’ choice of seating is voluntary, as he has no seating chart, and noted the strong gender discrepancy is not typical in Harker’s CS classes.

“[Last] semester was unusual, [with] only one [girl] in each section,” he wrote in an email. “[This] semester a third of the class (out of 18) is girls. Each girl handles the situation differently. Some work alone, and others are highly interactive with the other members of the class.”

AP CS teacher Susan King similarly encourages students to find work partners on their own. In her observation, students tend to favor working with members of the same gender.

“We work in partners a lot, and I want people to be comfortable with their partners,” King said. “Have I observed females particularly getting isolated by a bunch of males? Yes, I have. I’ve observed it in a number of schools. It hasn’t happened in a class of mine at Harker.”

King received her Bachelor of Science degree in CS from Montana State University in 1975, at a time when 19.8 percent of such degrees were conferred to females, according to the National Center for Education (NCES).

“I certainly know what [being isolated] is like,” she said. “I was often the only female in math classes or CS classes.”

That was 40 years ago, but the disparity continues. Mohindra’s experience as the minority gender reflects a broader downward trend of gender equity in technology.

As increasing numbers of women earn degrees in business, biology and physical sciences, the number of CS degrees received by women today is less than a third of what it was 30 years ago. In 2011, 18.2 percent of bachelor’s degrees in CS were given to women, compared to 37.1 percent in 1980, according to the NCES 2013 Digest of Education Statistics.

The term “pipeline” has become used throughout the industry with regard to how women become dissuaded from pursuing technology fields. Women are lost bit by bit through a pipeline that constricts as they move from early education through the subsequent years to employment age.

Harker positions itself as a “world-class institution” in the heart of Silicon Valley, the tech capital of the U.S. With 64 percent of last year’s female graduates self-reporting a plan to major in a STEM field, according to survey responses collected for The Winged Post’s college map, many already encounter or will go on to face gender disparities within these fields as they move along the pipeline.

Taking it to the next level

Senior Nitya Mani’s interest in STEM began at a young age, when her parents read her Richard Dawkins’ books on evolution. Love for math especially was a consistent part of her childhood. Since her years at Joaquin Miller Middle School in San Jose, she has done math research, taken a slew of advanced math and CS courses, and competed in math contests.

As Mani puts it, she “grew up on the math team.”

For the past semester, Mani, like Mohindra, had been the only female out of 13 in her advanced topics course in CS, Numerical Methods.

While most of the upper school’s classes have balanced gender ratios, there is a male majority in advanced CS courses like the ones Mani and Mohindra took.

According to Jennifer Gargano, assistant head of school for academics, enrollment in the upper school’s science departments such as biology and chemistry are relatively equal, but the courses following AP CS are 60 to 70 percent male.

Nationwide, The College Board has noticed a disparity between the genders in AP CS exams and a less severe one in AP Calculus BC exams. In 2013, 18.7 percent of AP CS test-takers and 40.5 percent of AP Calculus BC test-takers were female, according to the organization’s annual report.

“Historically there have been a disproportionate number of males taking AP exams in CS A,” said Amy Wilkins, The College Board’s social justice consultant, in an email interview. “Last year alone nearly 300,000 students with the potential to succeed in an AP course did not take one.”

Parental views can hinder young girls from STEM classes based on preconceived biases about whether girls can participate in the field.

Having grown up with a now 20-year- old brother, a 15-year-old brother and a 10-year-old sister, Chandini Thakur, grade 11, sees a different emphasis on STEM interests of males and females in her family. She plans on becoming a medical doctor, and her older brother studies computer engineering in college.

“My dad has already started working on getting my younger brother connected to people in engineering and not as much on my future career in the medical field,” she said. “It’s interesting to see that, because my sister’s already expressing an interest in engineering, and he’s not paying attention to that as much as he should be.”

As a teacher, science department chair and former AP teacher Anita Chetty has learned to pay attention to classroom dynamics. She recalls differences in reactions to girls’ and boys’ classroom participation in her years as a student.

“If boys made a mistake, people laughed it off,” she said. “If you were a female, you felt as though if you made a mistake it was not going to be funny. It was like, ‘You’re dumb.’”

Chetty’s interest in STEM led her to earn a B.S. in biology from the University of Calgary in Canada and two degrees in STEM education: a Bachelor of Engineering in education leadership at the University of Lethridge and a Master of Engineering in secondary science at the University of Portland.

As in Chetty’s observations, differences in attitudes towards disappointment divide students along gender lines. Her comments are rooted in research discussed in Dr. Diana Kastelic’s dissertation for the University of Denver, “Adolescent Girls’ Support for Voice in Education.” In her paper, Dr. Kastelic writes, “When boys fail, blame is placed on external factors, while success is attributable to ability. Surprisingly, girls’ achievement is attributed to luck and hard work, and failure is blamed on lack of ability.”

Mani refers to these and other subtle barriers against women pursuing STEM as “implicit discouragements.” She mentioned comments she received last summer from a Yale University professor alongside a male classmate.

“[The Yale professor] told the guy about the opportunities, and then he told me that I should look at the pre-med department, because that would be a better place

for me,” Mani said. While the professor’s motive was anyone’s guess, Mani said that hearing similar comments was commonplace and often disheartening. “There’s a lot of things that people do to implicitly discourage you. Now, it’s not so much [from pursuing] STEM, but to discourage women from pursuing pure STEM fields.”

For women and other minorities entering STEM, microaggressions, such as the one Mani faced, often result from unconscious bias.

From high school to college

After graduating from high school and beginning a major in STEM fields at campuses across the country, demographics in classrooms grow increasingly worse for females as they proceed along the pipeline to college.

Biology major Samantha Hoffman ’13 walks into the seminar room for her Computational and Mathematical Engineering (CME) class at Stanford University. What strikes her as odd is the composition of teaching assistants for the class.

“For both my CME classes, 100 percent of the TAs were male,” she said.

Hoffman, who plans to add a sub-concentration in neurobiology and a minor in creative writing, views the TA imbalance as an important issue to fix, due to female mentorship’s importance in encouraging female participation in STEM fields.

“The biggest problem is getting mentors, because without mentors, you can’t really get your advice. You can’t really get those connections to help you move forward in the industry,” Hoffman said.

As former upper school math department chair and middle school division head, as well as a math teacher at other public and private schools, Gargano stresses the importance of teachers as role models and guides. Throughout her study of math education during college, she was encouraged by professors who assumed she would go on to earn a master’s degree, even before she had planned to.

“It’s the teachers who really have so much power in terms of turning students onto a course that they thought they may not have interest in, or keep them loving a subject, too,” she said. “I think it’s all about the teachers.”

But finding a mentor for women in the worlds of academia can prove challenging on campuses like Stanford, where only three out of 54 of the CS department’s full-time faculty members are women, as Wingspan discovered by counting the department’s faculty on its website directory.

College and beyond: moving to the big league

Females who earn STEM degrees are faced with job placement as the next, and often most difficult, hurdle. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s 2011 Executive Summary of Women in STEM, females held only 24 percent of all working positions in STEM fields, even though females hold 48 percent of all jobs.

The disparity leads to disparagement, according to Tess Rinearson, a software engineer at blogging platform Medium in San Francisco and an attendee at Battle

of the Hacks 2014 at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, a programming invitational representative of over 50 events promoting innovation for college students.

“It’s something that people don’t want to talk about. It’s kind of the elephant in the room,” Rinearson said as one of five females out of 27 hackathon attendees in the room. “I’ve had lots of miscellaneous experiences where [I think,] ‘God, I wish there were more women in tech, because this behavior is unacceptable.’”

A Seattle native, Rinearson graduated from Lakeside High School and took classes at the University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Mellon before leaving college after a year to pursue a job at Medium.

Her experience as a 21-year-old female in the tech world has led her to describe the industry’s culture of microaggressions as “death by a thousand papercuts.”

Sometimes, the sexism can be much more direct. Last year, Rinearson experienced a more in-your-face example.

“I was supposed to be judging this hackathon. I talked to this team one-on-one, and I was really enthusiastic about this team’s hack,” she said. “As I walked away I heard one of them say, ‘She wants the d—,’ which is totally inappropriate.”

For women in careers that require an online presence, microaggressions often occur in the form of Internet harassment. Planetary geologist Emily Lakdawalla, who currently works as an editor and evangelist for The Planetary Society, an organization involved in advancing space exploration, discusses and promotes science through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

“When you’re on the Internet and you’re a female, you know it,” she said in a Skype interview. “It makes a difference. You get creepy comments. Initially I blew them all off, and over time it starts to get heavier and heavier, and you just don’t want to deal with them anymore.”

Writer and former physics student Eileen Pollack said combatting microaggressions that females bear while in a male-dominated field will help increase the number of women in tech. Pollack, who in 1978 became one of the first two women to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in physics at Yale, published “Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science?” in The New York Times Magazine in 2013. Later this year, she will publish her memoir, “The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science Is Still a Boys’ Club.”

“There are studies that say that women leave voluntarily because they want ‘people fields,’ and to this, I say, ‘There are no people in engineering?’” she said in a phone interview. “Engineers and chemists and computer scientists work in teams. There’s an idea that women walk away from the fields voluntarily, and that’s nonsense. [They are] already struggling under so many burdens every day where they feel they don’t belong.”

Females leaving or being unable to enter tech positions is not just an issue of social fairness but also an issue that impacts earning potential over a lifetime. According to Forbes, the highest paying jobs for college graduates are in engineering, with a median starting pay of $53,400. Even in the workplace, females earn less than their male counterparts; a 2012 American Association of University Women report stated that on average, a female in engineering makes 88 percent of what a male does when both are one year out of college.

Valuations of startup companies are at an all-time high, according to Forbes, with nearly 40 startups worth more than $1 billion in 2013. However, according to a 2013 report from Pitchbook, a data provider for venture capitalist markets, only 13 percent of venture capital deals had at least one female co-founder.

Seed accelerators like Y Combinator in Mountain View provide seed funding in exchange for an equity share in a prospective startup. Company partner Kat Manalac said Y Combinator received 5,000 applications last year, but only around one in four of the companies had a female founder. In response, Y Combinator launched its first Female Founders Conference last March with 450 attendees, involving a host of female founders sharing their stories. Another was slated for February.

“The big focus should be on how to get more women and people of color hired and in leadership positions at tech companies,” Manalac said in an email interview. “I’m encouraged because I’ve started to see a lot of smart people devoting their time to building solutions. The emphasis should be on action.”

Steps ahead

Mani and Mohindra both see themselves moving forward in the male-dominated field, confident that things will change by the time they are in graduate school.

“I think that the only way to break the gender gap is to get in when you’re the minority gender,” Mani said. “I feel fine, because there are going to be enough women around me. By the time that I get a Ph.D., there will be a lot of women with me, because I think it’s changing.”

As a senior next year, Mohindra plans to take Harker’s CS advanced topics courses Expert Systems and Computer Architecture, as well as the advanced mathematics topics courses Differential Equations 2 and Signals and Systems.

“I think within a decade, we’ll definitely have a lot more women in higher positions in STEM, and having those leaders as examples will provide yet another push for women to enter the fields,” she said.

Female alumnae have gone on to success in STEM fields. Forbes’ 2014 “30 Under 30” list in science and health care featured Surbhi Sarna ’03, who founded nVision Medical, a technology intended to improve ovarian cancer detection. Currently, several of the most prominent Bay Area tech companies are led by female chief executive officers such as Susan Wojcicki of YouTube, Marissa Mayer of Yahoo! and Meg Whitman of Hewlett-Packard. Sheryl Sandberg, chief operating officer of Facebook, and Mayer declined an interview with Wingspan.

At Harker, Gargano says she has explored some of the existing opportunities or initiative organizations that the upper school currently has in order to improve any imbalance, including WiSTEM (Women in STEM). Improvement, according to her, is still on the agenda moving forward.

“I think we have a lot of really accomplished females in those areas. Why wouldn’t we want to push forward those efforts?” Gargano said. “We can do better, and we should do better.”

Females already in the industry see hope for the future. Ruchi Sanghvi, who became the first female engineer at Facebook in 2005, helped develop the Newsfeed and Facebook Platform. She offers advice for females planning to enter tech fields to stand their ground but be ready for challenges.

“Don’t be afraid to voice your opinion. Don’t be afraid to ask for opportunities – raise your hand and ask for those opportunities,” she said. “When you’re offered a seat on a rocketship, don’t ask which one, just take it.”